Scan AmoureuxPierre Gauvreau and Janine Carreau at the Baron Gallery, Vancouver October 2011 - April 2012by Marshall SoulesMarch 2012In the 1933 edition of Minotaure (3/4), the Hungarian photographer Brassaï (Guyla Holasz) described Parisian graffiti as "l'art bâtard des rues mal famées." Brassai's fascination with bastard art and ill-famed streets was not a new obsession; at the time, he was earning his reputation as an acknowledged master of capturing his subjects in the moody chiarascuro of the city of light.

In the context of Minotaure, Brassaï's totemic photographs of gouged and scratched graffiti contributed to the Surrealist project of placing the archaic image at the heart of modernism. Discovering the primitive in the streets of Paris appealed to the ethnologist and documentarian in Brassaï, and expressed the kind of improvisation, spontaneity, and ad hoc happenstance Breton and others admired in pure psychic automatism. Brassaï, Graffiti, Paris, circa 1933 --> Vancouver's Baron Gallery exhibition of works by Québécois painters Pierre Gauvreau and Janine Carreau, deftly curated by Ray Ellenwood, resonates with the bastard art of graffiti. While Brassaï's incised graffiti is worlds away from current trends in urban street art, the thread of inspiration binds across time. The vibrant colour palettes, radical juxtapositions, apparent spontaneity, and wild gestures of contemporary street art advance - and comment on - the explorations of automatism. Here, art aspires to liberation, and resurrects that most fascinating of Surrealist stratagems - the cadavre exquis. The Baron Gallery exhibits a collaborative art, a dialogue, a chance to raise the dead and let the skeletons dance in resurrection and insurrection. Some corpses come to life. As Claude Gauvreau noted of a 1950 Riopelle exhibit in Paris: "[O]ne could imagine a happy catastrophe: a truckload of paint tubes blown up by a bomb" (Nasgaard 58). So "turbulent" (57) was Riopelle's painting style, it threatened to break out of the constricting frame and, in the words of critic Patrick Waldberg, "aggressively to carry on to the walls of the studio, on to the roof, onto the façade…" (58). Years later, Pierre Gauvreau and Janine Carreau paint under this Automatist totem and bring the street back into the gallery. This is not to say they are emulating the graffiti of the streets; this would be too bold a claim, for they have other things in mind. However, the quest for liberation, born of the Refus global in 1948, haunts both gallery and street. In another sense, the collection of paintings by Gauvreau and Carreau are a musical duet, where the performers listen to - and watch - one another with great attention and sympathy. Pitch and timbre, key and tone are playfully nuanced. The marks and traces of unique personality are never erased, always counted on to exert the right balance of presence and influence.

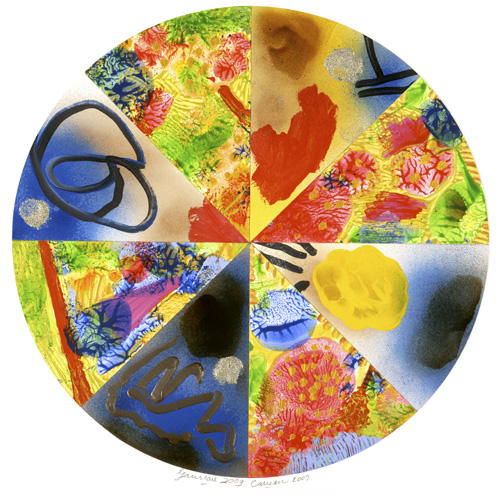

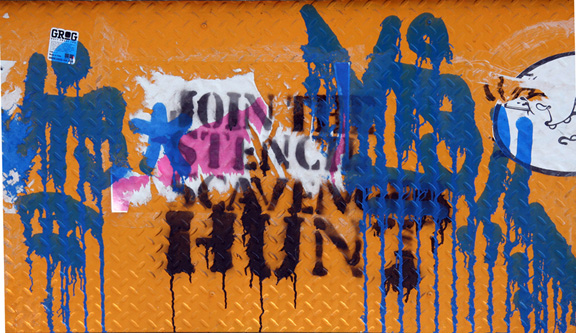

Nasgaard notes the "intuitive randomness" of Automatist practice: the "play of chance and unexpected accidents" as a way "to escape rational control and delve unimpeded into the uncharted depths of the subconscious" (5-6). This interplay of spontaneity and discipline leads Nasgaard to describe Borduas as a "mystic materialist" (14), where Marxist materialism is merged with passion for transcendence. Appropriately, Matter Sings (La matière chante) was the name of a 1954 Automatist exhibition. <-- Carreau/Gauvreau, "À jeunesse, jeunesse et 1/2" (To youth, youth and 1/2), 2009, mixed media on 8 panels, 51 cm diameter In "Comments on Some Current Words," Borduas suggests a way of reading the Automatist work as a "paranoiac screen": "a surface which, when stared at for some time, will clarify and fix ghostly shapes" (28). While it seems obvious from the name that paranoiac screen refers to a process of psychic projection, it also describes a method of working for Borduas, allowing him to execute his earlier gouache paintings more spontaneously in slow-drying oils: "First he filled in the prepared surface of the painting, the ground, giving it its predominant colour or tone in an automatic way. Once the paint was dry, he could use this ground as a paranoiac screen, responding to its visual incidents with a fresh set of marks and shapes that could be added on top, using the brush to draw" (Nasgaard 19). To contemporary street artists, the walls of the city are paranoiac screens in both psychic and material senses. The cops (in the head) are watching! As it happens, the Baron Gallery is located in the Downtown Eastside (DTES), a former Skid Road in Vancouver's logging heyday, and now home to the city's displaced and troubled refugees cheek-by-jowl against urban renewal and gentrification. Despite efforts to clean up these disreputable streets, the alleys of the DTES are still rich with the graffiti of the poor and marginal, including those artists-without-galleries who use the walls of buildings as their canvas. Their work is a collective improvisation marked by strange juxtapositions, eye-gouging colours, patterns of repetition that somehow connect, the best and worst of creative happenstance. This is the work of vandals and vampires, people of the night-time streets, creating without legitimacy, the scourge of the luminous city shining by the sea. Their collective (un)conscious acts upon the conscience of the hip material culture Vancouver wears elsewhere so stylishly. Graffiti and street art is a cadavre exquis that is both game and game over. The new global refusal.

Downtown Eastside Graffiti, Vancouver, Marshall Soules Why is Automatism - both as artistic movement and in its guise as the bastard art of graffiti - relevant today? Let's go back for a moment to the time of the original Refus global. In a letter to Fernand Leduc in 1948, Borduas declared his war on intention: "Intention must be pushed into the background, along with reason. Make way for the intelligence of the senses" (qtd. Nasgaard 54). As the Dadaists discovered in their time, our public discourse is a theatre for the corruption of reason and false compulsions of intention. People of faith turn to their various beliefs as a refuge from repressive politics and social inequities. Graffiti and street art are a global refusal of this corruption of intention and bastardization of reason, replacing it with a riot of colour and celebration of the archaic and anarchic energy of humans protesting. This exhibit at the Baron Gallery thus requires some viewing agility to see the work of Pierre Gauvreau, the work of Janine Carreau, and the synergy of the two artists working toward a shared vision. The show is an Inuit sculpture of the old-style - with no flat spot on the "bottom" - held in the hands and turned this way and that to reveal all its delicate contours. There is no up or down - though the paintings do need to be hung the right way up! The demarcation between land and sky has been obscured and we are in a realm of all the senses. Or to take another analogy, the work is a garden whose beauty and harmonies emerge with trial-and-error, planting and replanting - a labour of love in dialogue with the seasons.

Carreau/Gauvreau, Echo d'un autre monde VIII, 2009, mixed media on 21 wood pieces, 81 x 102 cm The exhibition is an homage between the artists, and by a curator fascinated by the play of imagery up and down the scales of consciousness. Ellenwood's academic background in the Surrealist movement, his knowledge of the égrégore - the spirit of the cohort - of the Montréal Automatists, and his facility with language make him a trusted guide. That he was closely assisted by Janine Carreau in his selection of 47 works from a lifetime of artistic production contributes an unmistakable air of intimacy and insight, even to those uninitiated in the workings of abstract expressionism. Pierre Gauvreau passed from this life on 7 April 2011, six months before the Baron Gallery exhibit opened. But his spirit lives in the selection of works by Carreau and Ellenwood, appropriately titled "Art = Libération." Their homage testifies to an artistic life dedicated to liberation from social repression and artistic dogma, the agenda of the famous Réfus Global, of which Pierre Gauvreau was a signatory. More immediately, the exhibit is an homage to the love between Pierre and Janine, together since 1976, to their social network, and especially to that particular magic of collaboration most cunningly orchestrated by the cadavre exquis. (For a detailed discussion of the cadaver exquis in the hands of Carreau and Gauvreau, see Ellenwood's "Le Cadavre Exquis est Bien Vivant et Se Trouve à Montréal.") One sees in the works of Janine Carreau the impulse to build relationship, foster community, and celebrate the rhythms and cycles of nature. While Pierre's work may flirt with anthropomorphism and the surrealist landscape, many of Janine's works include images of loved ones, references to cultural heroes (John Lennon, Leonard Cohen, Marilyn Monroe), and offerings to the animating spirits of nature. Liberation through art is to be experienced in the sustaining nurture of the landscape and the proliferating garden, emblems of an égrégore - spirit intact - of a community of fellow travelers. ![Carreau/Gauvreau, La jeunesse est en nous et nous sommes la jeunesse [Youth is in us and we are youth], 2002, acrylic on canvas, 112 x 173 cm](jeunesse.jpg)

Carreau/Gauvreau, La jeunesse est en nous et nous sommes la jeunesse [Youth is in us and we are youth], 2002, acrylic on canvas, 112 x 173 cm Convulsive Beauty: The Painter's Song"Looking at the pictures in this exhibition your mind will be blank. You won't even be allowed the idea of a picture. These paintings don't correspond to a landscape, nor to a still life nor to any scene you're familiar with, nor even to a geometrical abstraction. Thus, with all your mental habits put to flight, unable to make any kind of visual contact, you will have the uncomfortable feeling of a serious illness, a painful and needless amputation, a frustration." (Borduas, "Comments on Some Current Words" [Picture] 1948)In Égrégore: A History of the Montréal Automatist Movement, Ellenwood quotes Guy Viau on the spirit of revolution that animated the founders of the movement: "The story of Automatism begins in a feeling: an obscure and exasperated feeling of revolt against what the rational and mechanical civilization of today is doing to mankind, and to French-Canadians because of a particularly stifling historical situation. But above and beyond that revolt, Automatism is a story of a poetical perception of life and world; a liberation of the powers of imagination and sensitivity" (3). Borduas associated this quest for liberation with children: they "opened wide the doors of Surrealism and automatic writing for me. The painterly act in its most pristine state had at last been revealed." Both then and now with the Automatists, there is a sense of play under the influence of children who dip into the unconscious more fluently, perhaps, than adults ruled by intention. Children, masters of combining what they have at hand to create objects of fantasy, follow their own rules, their protocols of recombination, not so much to produce an outcome but to act out and perform. As a teacher, Borduas valued the artistic production of children, basing his ideas of improvisation and creativity - like the theatre practitioner Jacques Copeau - on the play of children: "the child who, in sheer bodily delight, jumps and shouts for joy on a spring morning: that is where we find the origin of exultation" (Copeau 5). It wasn't always clear what Borduas meant by the "painterly act" before Clement Greenberg brought his analytic skills to bear on Abstract Expressionism, though Borduas uses a telling analogy with music in the following: "[T]he work of art must be produced in a constant state of becoming, so that instinct, from which the song flows, may express itself continuously as the work is being executed. The painter's song is a vibration imprinted on matter by a human sensibility. Through it, matter is made to live" (qtd. Nasgaard 12). Borduas distinguished "painterly thoughts" - "having to do with movement, rhythm, volume and light" - from "literary ideas…only useful if they are transformed plastically" (14). Under the direction of Borduas, then, the challenge for the Automatist painter was to shift away from imitating the pictorial givens of the world - forget about verisimilitude! - and concentrate on the plastic qualities of the medium, now associated with music and the play of children, to embody the feelings and instincts of the artist. Through a kind of empathy with colour, movement, rhythm, volume, and light, the viewer would be transported to a psychic space unencumbered by the intentional traps of a phenomenal, political reality. In the heady days of the Refus global, Pierre Gauvreau described his own creative process in terms largely consonant with Borduas: "The forms I paint do not come from rational calculations but from the free play of the unconscious" (qtd. Ellenwood Égrégore 44). In response to Tancrède Marsil's question "During the process of creation, do you pay any special attention to the proper juxtaposition of values?" Gauvreau replied: "During the creative act, I am not preoccupied with anything like that. My sole concern is the necessity of maintaining the integrity of my feeling at its highest pitch. Of course, once the work is finished, I can judge it plastically. If it can't be justified in that way, looking at the unity of light and composition, the structural rigor of its objects, I reject the painting as a sign of my efforts having failed" (44). As the Dadaists had done before them during a previous war, the Automatists rejected false rationality and attempted to replace intention - self-conscious and inauthentic - with what Borduas referred to as "necessity," those energies beyond the control and manipulation of intention: compulsion, drives, spontaneous inspiration, instincts - the "unpredictable, necessary order of spontaneity" (Refus global 20). These gut instincts arising from the body make just as much sense as instrumental music. "The surrational act takes risks with unknown possibility; reason reaps the benefits" (Borduas, "Comments on Some Current Words" 33). Perhaps Breton, the Surrealists, and the Automatists idealized the ability of children and primitive peoples to tap into the unconscious. (As Breton wrote in 1935, "This search tends more and more to liberate instinctive impulses, to break down the barrier that civilized man faces, a barrier that primitive people and children do not experience" [qtd. Ellenwood 169].) Or perhaps children and primitive peoples like to play: to take what they have at hand and make it into something that could be. We make paper airplanes, and use sticks for swords. Anthropologist Victor Turner argues that the domain of play is ruled by the trickster archetype, since play is all about transformation, even of moribund cultures. And play is highly complex cognitively, requiring intricate neural switching in the brain's limbic system to integrate physical impulses, emotional states, and higher cognitive powers. Turner's formulation of play as cultural transformation has much in common with Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi's widely-known concept of flow, a form of optimal engagement with all of one's faculties. For Csikszentmihalyi, to reach a state of flow the challenge of the task at hand must be high and so must the level of skill required to meet that challenge. Anything less leads to boredom and apathy. Is this how art equals liberation? The automatism of inspiration and the automatism of execution allow us to be present at the "birth of the world" in which mankind, birds, flowers, stones, air and water participate in nothing but the "convulsive beauty" of the mysterious and terrifying gravity of prophetic advances. (Fernand Leduc to Andre Breton, 1948, qtd. Ellenwood Égrégore 177). Out in the bastard streets of the DTES, nocturnal nomads and vandals sow their tags with hardly a thought of social decorum or private property, concentrating only on the style of their gesture and its precise placement on the urban canvas. Or, with time so short, they throw up their pieces in garish colours running rampant over a ground of plaster, concrete, wood or metal. They are writers, with a revolutionary message: "I am here now. You do not own the streets or control the messages. This is my art, like it or not." A total refusal to play by the rules. Tricksters on the margins of culture, forging a new collective mythology distinguished by its convulsive beauty. "Hand in hand with others thirsting for a better life, no matter how long it takes, regardless of support or persecution, we will joyfully respond to a savage need for liberation" (Refus global 20).

Stencils and Folk Art"As Pierre turned to working with stencil effects and sprayed colours in the late 90s, Janine's acrylics became increasingly bold and textured. Both pushed the boundaries of "good taste" using collaged glossy papers, sparkles, and gaudy colours, like the patenteux, the Québec folk artists they so admired." (Ellenwood, Life in Bright Colours)Graffiti is the cadavre exquis of the global zeitgeist, the chance juxtapositions of an over-active subconscious screaming for equal airtime with the forces of materialism and conformity. It is a new global refusal, recycling city walls and industrial materials in a massive détournement. Street art is urban folk art. It makes use of "patterns that connect," the term Carl Schuster used to describe the "patterns of organization underlying traditional arts" (9). Reading these pan-cultural messages requires pattern recognition, "foreswearing context in favour of an unflinching look at the designs themselves" (9). The checker device, labyrinth, hopscotch, gaming boards, arrows, dots and circles, stars, waves and zigzags, triangles, and all manner of archaic patterning speak across cultures and times of our common humanity. Intricate patterns of lace resonate across cultures, from Celtic knots and manuscript illuminations to henna tattoos.

The materials of folk art / street art are not precious; they are serviceable, industrial materials to keep the water out and the rust from accumulating too quickly (since rust never sleeps and water is the universal solvent). The yellows and reds of municipal signs and traffic lines suggest a utilitarian desire to get the message across to even the most somnolent and distracted citizens. (Peter Gibson's work in Montréal as the stencil artist Roadsworth is worthy of note for its sewing of thought-provoking confusion.) Stencils are quick, repeatable, and surely at home in the empire of signs. The street artist Némo says, "What interests me is that the stencil is 'open': one person will see one thing, another something else." Or the artist Western Cell Division: "Street stencils are beautiful little booby-traps of information lying in wait; aesthetic gifts left behind as urban folk art, simultaneously revealing and concealing their purpose" (Manco 6). The meanings of graffiti (from sgraffio, to scratch, and graphein, to write) are no longer limited to scratching on the walls of caves or buildings, but now include marker pens, spray paint, brushes, stencils, cut-outs, stickers, and even light projections. The French technique called pouchoir, writes Christian Manco, "was an extremely costly and laborious process in which a design was built up with metal stencils, each coloured by hand using gouache paint, creating the illusion of watercolour or oil paintings" (8). This in contrast to the strategic slap-dash of military and cargo cult stencils, all mass production, utility and high visibility. "Stencils are more self-conscious than the spontaneous tagged graffiti messages or the coded confidence of hip-hop style….

<-- Stencil, Vancouver, photo M. Soules Stencils provide windows onto their substrate (metal, stone, concrete, wood and paper) and are integrated into the visual surroundings and textures for maximum utility. Placement is strategic and crucial to success. In the making, figure and ground are reversed, like a photographic negative. Arrows indicate direction and force. Lines mark out boundaries. Consistency is important for the effect of repetition and identity. Above all, stencils predetermine pattern and form as a counterpoint to the wild expressive gesture of marker and spray can, making matter sing. Seeing Through![Gauvreau, L'oeil du cyclope condamné [Eye of the doomed cyclops], 2004, mixed media on canvas, 122 x 61 cm.](cyclope_gauvreau.jpg)

"Their symbiosis is the union of two fiercely independent but inseparable beings. Their artistic synergy is a playful self-realization. They reciprocate each other, like two playing children, automatically and unconsciously, astonished by the echo reverberating from infinite spaces." (Sonia Denault, director Galerie Michel-Ange, Échos d'un Autre Monde 6)Or is this a different kind of liberation for Gauvreau and Carreau? Not of total refusal but the flowing affirmation of a garden, with its beauty beyond the reach of rational analysis - it just exists! Is this creativity that nurtures friendships and communities, requiring attention to natural rhythms, physical intuitions, and patience over the seasons? In these works there is the sense of seeing through the layers of a palimpsest, as the shaman Don Juan saw through the illusions of reality in his teachings to Carlos Castenada - another world of shape-shifting, home of the trickster Nagual with its animal counterparts. In Gauvreau's works after 1995 viewers might see a falling off of visual acuity and manual dexterity - something akin to Matisse's later works with the cut-outs. Such a perception, however, would obscure the evolution of a changing vision and revised testament. As Ray Ellenwood comments: "There is a kind of youthfulness and vitality in his work [after 1995] that completely belies the conditions under which it was made." Gauvreau, L'oeil du cyclope condamné [Eye of the doomed cyclops], 2004, mixed media on canvas, 122 x 61 cm --> What does the eye of the doomed Cyclops see with its singular vision? Static, TV noise, an infinite universe of radio waves waiting for a listener, patterns in Morse code, a totem to perception and communication, breasts and knobs for tuning in to other worlds? This is a machine for communing with mythic visions. "[A] myth is the most perfect symbol of a mysterious, clear and constant reality. A symbol expressing the known and unknown of this object itself, placing it in total context." (Borduas, Comments on Some Current Words, 28) ![Carreau. Vous me pardonnerez bien autre chose aussi [Pardon me for not apologizing for other things as well], 2000, acrylic on canvas, 183 x 91.5 cm.](pardonnerez_Carreau.jpg)

We see an assured colour palette and confident sense of composition, seemingly spontaneous, but with evident calculations. Here is an active, inventive sensibility steeped in automatist protocols of non-figurative expression, plastic dexterity, and transcendental vision - the inner light of a marvelous, vibrant world. There are patterns that connect: the intricacies of elegant lacework with its domestic resonance, the rhythms and insistence of stencils, the relaxed craft of the patenteux, and the exploration of alternate notions of beauty, and reality. Ellenwood quotes Gauvreau on the influence of the Québécois folk artists: "They gave me a kind of aesthetic permission, an audacity I might not have had in my use of colour and also form, the forms we label beautiful or ugly, ancient or contemporary. I don't worry about those things any more. I don't think I used to, intellectually, but we develop conditioned responses to our own work" (Artist Statement). In Janine Carreau's work we finds maps of the landscape - fields, lakes, horizon, fences - animated by Castenada's perception of mystical power and potential for transformation. Or recalling Leonard Cohen's "There is a crack, a crack in everything / That's how the light gets in" ("Anthem," The Future 1992). This is art that turns vision inside out and upside down; we see through the patterns and layers of light to enter a different world, free of the usual conventions, luminous and joyful. Without apologies! <-- Carreau. Vous me pardonnerez bien autre chose aussi [Pardon me for not apologizing for other things as well], 2000, acrylic on canvas, 183 x 91.5 cm Scan AmoureuxAs with graffiti on urban walls, the cadavre exquis works convey their messages through their form. These works are intimate, the marks of people in community, depending on one another, reaching agreement about method, putting private ownership up for grabs, always leaving room for synchronicity and chance. This is how society should be, claim the artists. This is the kind of art that leaves room for liberation. And always the music, the interplay between sensibilities. These are diagrams, maps of the interior, emotional life, filled with hopes, dreams, love, companionship, fears, and disappointments. The images are often totemic for Gauvreau: interlocking symbolic forms animated by gestures of colour and the effect/affect of layering up paint on a textured surface, layers to see through and with, lenses that open up and restrict vision alternatively. ![Carreau/Gauvreau. Scan amoureux [Loving scan], 2009, mixed media on 8 panels, 51 cm. diameter](scan_amoureux.jpg)

The circular cadavre exquis is a mandala. While each segment bears the unmistakable fingerprints of the individual artist, assembly into a unified work creates a magical mirror for reflecting the inner dynamics of the viewer's psyche, a paranoiac screen. We see what it is to us. The Scan amoureux is a machine for scanning, surveying, taking the pulse of the relationship, which just happens to be a gorgeous and fantastic landscape. ReferencesBorduas, Paul-Émile. "Total Refusal." Total Refusal / Refus global: The Manifesto of the Montréal Automatists. Translation and Introduction Ray Ellenwood. Holstein, ON: Exile Editions, 2009. 1-20. ---. "Comments on Some Current Words." Total Refusal / Refus global: The Manifesto of the Montréal Automatists. 23-33. Carreau, Janine and Pierre Gauvreau. Échos d'un Autre Monde. Catalogue, Galerie Michel-Ange, Montreal, 2009. Ellenwood, Ray. "Artist's Statement: Pierre Gauvreau." Email to Baron Gallery, November 16th, 2010. ---. Égrégore: A History of The Montréal Automatist Movement. Holstein, ON: Exile Editions, 1992. ---. "Le Cadavre Exquis est Bien Vivant et Se Trouve à Montréal" (The Exquisite Corpse is Alive and Well and Living in Montréal), in Échos d'un Autre Monde, Catalogue, Galerie Michel-Ange, Montréal, 2009, 156-174. Manco, Christian. Stencil Graffiti. London: Thames and Hudson, 2002. Nasgaard, Roald and Ray Ellenwood. The Automatiste Revolution: Montreal, 1941-1960. Vancouver, BC: Douglas & McIntyre, 2009. Copeau, Jacques, "A Sacred Origin," Copeau: Texts on Theatre, ed. and trans J. Rudlin and N. Paul, New York: Routledge, 1990, 5. Schuster, Carl and Edmund Carpenter. Patterns That Connect: Social Symbolism in Ancient and Tribal Art. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996. Total Refusal / Refus global: The Manifesto of the Montréal Automatists. Translation and Introduction Ray Ellenwood. Holstein, ON: Exile Editions, 2009. Turner, Victor. "Body, Brain, and Culture." The Anthropology of Performance. New York, PAJ Publications, 1988. 156-178. © 2012 Marshall Soules. Fair dealing applies. |

Stencil style is graphically associated with the sort of functional type long found on packaging, and is thereby also associated with authenticity, natural materials and an authoritative message" (Manco 11-12). The screen print stencils of Warhol and Rauschenberg deconstructed the materials and techniques of high art in the service of Pop. Italian fascists used stencils of Il Duce for propaganda.

Stencil style is graphically associated with the sort of functional type long found on packaging, and is thereby also associated with authenticity, natural materials and an authoritative message" (Manco 11-12). The screen print stencils of Warhol and Rauschenberg deconstructed the materials and techniques of high art in the service of Pop. Italian fascists used stencils of Il Duce for propaganda.